Susanna Raganelli's Epic World Championship Triumph That Led to Horrific Cries for the Banning of "Women Drivers from Karting"

The Untold Story of the Greatest Female Race Driver of All Time

Will we see the first female FIA World Champion crowned in the coming years? No.

Will we see the first female FIA World Champion defend her title on the streets of Monaco in the coming years? No.

Why? It’s not because I’ve become a raging chauvinist - I'm just stating a fact. The reason these statements are true is that it’s already happened.

If you’ve followed me for a while, you’ll know exactly who I’m referring to because I’ve written and done videos, but if not, allow me to educate you. Her name is Susanna Raganelli, and she was the 1966 World Karting Champion.

While I don’t like to reference ‘F1 drivers’ when celebrating someone’s achievements, it seems necessary to add this perceived ‘credibility’ for those unfamiliar with the great sport of karting. So, if you don’t know her, here are a couple of names you’ll recognise. She beat Keke Rosberg and Ronnie Peterson. Now, if you’re like me, you’ll appreciate that the real achievement wasn’t just beating Peterson (one of the pre-event favourites for the World Chamionship in ‘66) but also besting the likes of Mickey Allen, Guido Sala, Goldstein, and Pernigotti. As we’ll see, no one came close to her at the 1966 World Championship, much to the frustration of Karting Magazine at the time.

The reason I find this important - and why I’ve written about Raganelli so often - is that I’m utterly baffled by the lack of attention her achievement receives in modern motorsport. She was the first, and remains the only, female world champion in an FIA-accredited World Championship. Yet, you’ll hardly see her mentioned anywhere. Karting does a terrible job of celebrating its history, often foolishly using F1 drivers as measures of relevance and success. It’s as if she never existed.

As we’ll discover, the British karting press wasn’t supportive of her - that’s putting it lightly. She disappeared from karting after 1967, and aside from racing in the 1975 Monaco Ladies' Race, it’s difficult to track what she did afterward. Hopefully, she’ continues to live an incredible life, and I would understand if she wanted to avoid attention, especially given what was written and done in 1966. But the near-total blackout of her success - which involved winning major events in front of thousands of people and ecstatic Italians - is downright bizarre.

Yes, I believe there are strange attitudes in the motorsport world regarding karting, and they’ve been there since its very inception. But even with that in mind, you’d assume that with all these programs aimed at getting girls into karting, you might find one or two references to the sport’s female World Champion. But I can’t find many - if any.

While Suzy’s World Championship remains the only one won by a woman, success in karting for women isn’t rare. I could list an enormous number of top female drivers: Mary Hix, Val Nixon, Charlotte Hellberg, Sophie Kumpen, Ella Stevens, Lorraine Peck, Jeanette Peak, Cathy Muller, to name but a few. The cliché that “everyone is the same with a helmet on” is well-trodden but true. I don’t want this to be a ‘look, a woman won’ piece - the story itself is packed with enough drama that it’s worth telling in its own right.

So let’s dive into Suzy’s story and give it the attention it finally deserves. If the rest of the motorsport world won’t, I will. What we know about her actual racing is largely filtered through the lens of the British media, who weren’t her biggest fans - but march forward we shall.

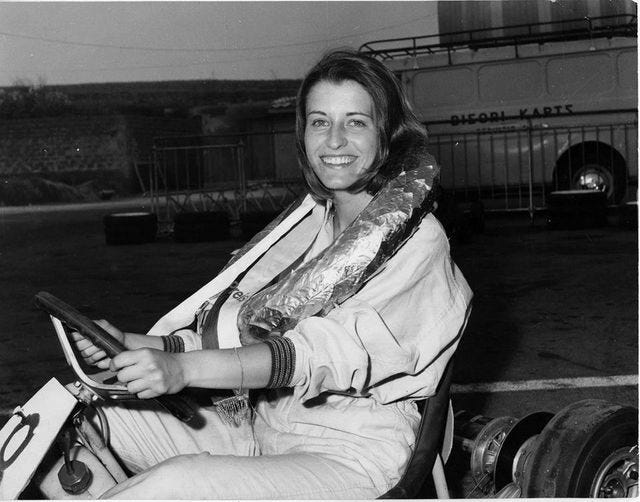

Daughter of Targa Florio competitor and Alfa Romeo dealer Cesare Raganelli, Susanna was born in 1947. She is arguably more famous for being the first Italian owner of a Stradale 33. Her mechanic was a certain Franco Baroni and she ran Tecno chassis with Parilla engines. In 1965, she took the karting world by storm. This is that story.

Introduction to Suzy the ‘Crafty One’: European Team Championship 1965

The first round was held in the Swiss town of Vevey, in the market square - quite an astonishing location for a kart race. Historic buildings nestled next to Lake Geneva, with an incredible landscape surrounding it. Thousands of spectators lined the circuit, some even climbing trees to get a better view. The European Championship in the sixties worked differently than it does today. International karting was made up of national teams, and the European Championship crowned countries as winners, not individual drivers, as was the case with the World Karting Championship. Each country would nominate four drivers to compete for the title.

The youngest member of the British team, David Salamone, once described to me how he and his mechanic drove to Vevey in an MG MGB, with his kart hanging out the back. An image that I find incredible and completely unimaginable today, considering the fleets of HGVs that now dominate international karting paddocks.

A few years later, Salamone would appear in The Italian Job, driving the red Mini, after being hired to source all the cars for the film. What a life! Vevey, however, was really a successful ‘Job’ for the Italians, as they swept to victory, led by reigning World Champion Guido Sala. Suzy, in particular, caught the eye of a British team member who described her as ‘crafty’ due to her tactics in one of the races.

In one of her heats, Suzy slowed the field down so much that several competitors "oiled up." The Italian team’s technical know-how was on full display here: their carburetors could handle the slow speeds, and as soon as Suzy accelerated, she left most of the field behind. If you're unfamiliar with the 100cc two-strokes used in karting, they really don’t like going slow! A close battle ensued with British legend Mickey Allen, but despite appearing a tad quicker, he couldn’t get past her.

Karting Magazine noted that a prerequisite for being on the Italian team was being able to restart your kart if needed. This led to an increased focus on low-speed carburetor tuning. Whether any of that is entirely true, who knows.

In the final, Raganelli finished 2nd behind her teammate Constantini, with Peterson in 3rd. The Italians were the overall team winners. If there had been any doubts, Suzy and the Italians made it clear they meant business, and she had certainly caught the attention of observers.

Round 2, held at Leidschendam in Holland, was won by Belgium, with Italy finishing second. Once again, Raganelli was at the front, battling for victories in all her heats. In the first heat, she lost out to British driver Buzz Ware on the last lap. In the second heat, Ware spun out while chasing her, and she claimed the win. In the third heat, teammate Eleonori supposedly held back the chasing group, allowing Raganelli to secure another victory. The final was won by Guido Sala, with Raganelli finishing 26th, most likely due to a retirement. Belgium left the event as overall winners, but Italy retained the championship lead going into the next round at Villacoublay, where the Italians would ultimately be crowned champions.

The “Talented Italian Girl”: The European Team Championship 1966

What a sight it must have been. As Raganelli crossed the finish line at the first round of the Vevey European Championship, taking the final race win, ‘La Suzy’ was greeted with such a popular victory that police had to use batons to hold back thousands of Italians celebrating. It’s almost incomprehensible for modern karters to even imagine an event with fans, let alone enough to require Vevey’s police force to intervene.

She didn’t qualify on pole. Time qualifying took place over two laps, not one, and this honour went to her longtime rival Ronnie Peterson, who posted a 1:12.00 vs. her 1:12.30.

In words that Karting Magazine would later recant somewhat, the ‘talented Italian girl’ won her first two heats. In the second, Mickey Allen put the squeeze on her into the first corner but ended up colliding with the hay bales and losing several positions. The third heat saw Brit Bobby Day get in front at the start and manage to keep her behind, which, given Suzy's usual dominance, was a pretty impressive achievement.

With Peterson winning all his heats, the stage was set for a proper old-school showdown. At the start, the pair got away cleanly. Back then, races were long - 40-50 lap finals were the norm - and as the race wore on, Peterson reportedly tired and had to concede to Suzy. La Suzy won for Italy, and the Italian crowd went wild.

Round 2 was held in the market square of Lissone, Italy and within walking distance of the Monza Grand Prix Circuit. Qualifying was close, with Peterson on pole with a 1:26.8. Raganelli was back in 4th, two-tenths off Peterson’s pace.

Raganelli finished behind Pernigotti in her first heat, as the Italian team cemented their dominance. After some initial issues at the start, where officials thought Pernigotti was starting too fast, the second heat became more eventful. Once again, Raganelli was behind Pernigotti but started bumping him in some corners. Out of frustration or fun? Who knows. But it alarmed Gordo Sala, the team manager, enough that he signalled her to back off, which she did. By this point, Pernigotti had let her through, but she dutifully allowed him to retake the position. Poleman Peterson won all his heats and was the man to beat. In the final, Peterson continued his dominant form, with Pernigotti second and Raganelli third. The Italian team accumulated enough points throughout the meeting (Peterson being the sole Swede in a top six vs four Italians) to win overall and maintain their lead in the championship.

Unfortunately, we must skip Round 3 as I don't have a report, but heading into Round 4 at Villacoublay, France, the Italian team had maintained their commanding lead in the championship. In Raganelli’s first two heats, she finished 2nd in both. However, in the third heat, she crashed with Boshuis and Peterson. The track was very hazardous due to the greasy and wet conditions that plagued the meeting. The final was won by Staalduin, with Golstein second and Engstrom third. Raganelli spun out of the final, but Italy had such a commanding lead in the championship that it didn’t matter. They were once again European Team Karting Champions!

Pure Domination: The 1966 Karting World Championship

“Ban women drivers from karting” was not the statement I expected to read in the sub-headline of Karting Magazine’s report from the 1966 World Karting Championship at the Klovermarksveg track in Denmark. The statement was followed by, “if having them means giving them special treatment to the detriment of the sport.” Oh boy, this was not how I thought this was going to go. My source, Karting Magazine, was somewhat biassed.

I had been aware of the infamous ‘Down with Suzy’s Knickers’ T-shirts worn in the paddock by a rival engine manufacturer, which must have been awful to witness, but this was a shock. I had hoped to write in detail about the 1966 World Championship, but now I must navigate this with a bit more care.

The issue lay in the fact that Raganelli utterly demolished everyone, by a significant margin. The reason? According to Karting Magazine, it was because she had a huge power advantage. Sure, they felt she courted favour with the officials, which was the reason for the “ban” suggestion but the annoyance seemed more to do with the perceived mechanical advantage, something they had never mentioned in the two prior years of reporting.

It’s become increasingly common to remind people that karting, at the elite level, isn’t a single-make spec sport - it’s development-focused. That means multiple engine manufacturers competing to outdo each other. Getting a ‘good engine is part of the game. If you can’t get one, do better. Karting Magazine’s attitude betrayed the spirit of competition. This was only a year after Jim Clark and Lotus completely dominated Formula 1.

The event was open to non-homologated engines, allowing for substantial development opportunities. Yet, only Komet brought something new. Suspicions of twin-cylinder engines were unfounded. The Parilla GP15Ls were so dominant that Komet had to try to improve upon the K77. Details of their development were scarce, and it didn’t matter in the end, as Bruno Grana’s Komets weren’t able to overhaul the Parillas.

The criticism that Raganelli had the best engine was absurd. This is motorsport - every driver is trying to get the best engine possible. It’s part of the game. Criticising her for that is like criticising Jim Clark or Graham Hill for having the best car with Lotus. It’s silly.

I’m all for examining whether any driver receives unfair favours, but Karting Magazine’s editor seemed to drown his valid points in personal bias. Raganelli was simply a pioneer of modern karting, with her team doing everything right.

In timed practice, Raganelli posted a 1:05.1 - half a second faster than Hezemans' 1:05.6, who was second. The marker was set, and Raganelli had already shown her dominance. This was a demolition job. Karting Magazine soon started mentioning Raganelli’s power advantage, likely fueled by the struggling Brits. The fastest British driver, Mickey Allen, was back in 17th, 1.1 seconds off her time.

Now, the heats became chaotic. In one, a Dutch team manager stormed onto the track, inside a corner, and tried to grab a driver he believed was unfairly blocking his own driver. In a later heat things became even more bizarre when an ambulance entered the live track. Sala, the reigning champion, had tried a risky move and was thrown from his kart. Before he even hit the ground, the ambulance was speeding through the track, bewildering everyone who had to avoid driving into a car circulating the circuit.

What about her rivals? Ronnie Peterson, the favourite for the title like Sala, spun out from one of his heats while leading, severely denting his hopes for a good grid position in the final. Pernigotti, another title contender, was caught in a major pile-up as well. Engstrom, who qualified third, was the only driver to provide any real threat to Raganelli. A relative unknown before the event, he excelled throughout the heats and into the finals.

Raganelli won all her heats, but not without annoying Karting Magazine. In the first heat, Cai Lundberg tried a move around the outside of Raganelli but ended up in the tire wall. According to Karting Magazine, the "nonsense" that had been building in the European rounds (though not much reference to this exists in other reports beyond the 1965 European Championship, when the Italians employed very slow rolling laps) began. On the rolling lap, Raganelli apparently stopped, and her mechanic, presumably Baroni, wiped her visor. She then rejoined the front of the grid and took off. Her competitors were likely frustrated, but if it was within the rules, it showed her and her team were simply ahead of the game.

In her final heat, Pernigotti latched onto her, posing a genuine threat. The female Danish contingent cheered for Raganelli during the heat, but the Italian team cooled off the battle, and Pernigotti fell back. That heat saw Bobby Day get tangled with Ihle, and they spent four laps connected, inexplicably not stopping to untangle themselves.

Raganelli would start on pole for the first of three finals which would become incrementally longer, with the last being a brutal 50 laps.

Disaster seemed to strike as she stopped at the hairpin during the rolling lap. Leif Engstrom, her main competitor, couldn’t have asked for better luck. But she got going again and rejoined her starting position. Karting Magazine hinted that allowing the field to roll around again was due to favouritism. It’s worth noting that in 1979, Karting Magazine reported that when Senna had a similar issue in a final, the field was held back he was allowed to change carburettor. No one was calling for a ban on drivers after that however..

When the final got underway, Engstrom initially led for about four laps before Raganelli took over. Brit Mickey Allen was competitive, threatening Engstrom for second, but a puncture took him out of contention. Raganelli won, cruising toward World Championship glory.

The second final began similarly, but with Engstrom holding onto the lead for 15 laps. Any other year, he’d have been champion, but once again, Raganelli was unstoppable. A crash involving Pernigotti, Allen, and a few others caused drama, but everyone walked away fine.

The last final of the day was an endurance test. Raganelli kissed her mother, Baroni checked the kart, and everyone waited - classic Raganelli mind games, much to Karting Magazine’s annoyance. Once again, Engstrom led from the start, but this time Raganelli passed him on lap one. She won the final by 30 yards. Mickey Allen impressed with a superb drive from 15th to 5th.

Susanna Raganelli was the 1966 World Karting Champion.

Despite her incredible and undeniable success winning the World Championship in addition to her European and Italian National Championship victories, Karting Magazine no longer called her the ‘talented Italian girl’ but dismissed her driving as “not expert,” effectively attributing it to “daddy’s money.” Their biggest grievance wasn’t her lack of ability but the “irritating manifestations connected with her being a girl.” Nothing she did was technically illegal, but they followed their regrettable words with “If this is what happens to karting when women race, then we would rather they be banned, and the sport return to what it was intended to be.”

What karting was “intended to be,” I’m not sure. But Raganelli and her team destroyed the competition, and these unfortunate comments were thankfully met with well-deserved criticism.

A Letter and the Infamous “Down With Susy’s (Knickers)” T-shirt

Mr. Simon Melrose of South West London accused Karting Magazine of sour grapes, and to their credit, the magazine published his letter. Melrose pointed out that the accusations about Raganelli having the best equipment were not levied against the British drivers, who could afford the best engines in their respective national competitions. He further argued that the comments about her father’s wealth misrepresented her skill, as the British had the best motors Komet could supply.

As Melrose noted, the tactics Raganelli employed were standard psychological preparation for competition, and drivers should not be in a position where such strategies affect their performance.

He concluded by stating that this World Championship would harm the British reputation and requested an apology from what was otherwise an excellent magazine.

Karting Magazine did not issue a direct apology in response to the letter in the issue. Instead, they published an image of an individual wearing a “Down with Susy’s (Knickers)” T-shirt that was available for purchase. Yes, they really did that, and it is horrifying.

Raganelli did appear as a top-billing under the Roll of Honour in 1967’s Going Racing by Alan Burgess. Whether this was conciliatory moment, I am not sure, but one hopes so.

Nearly a Two-Time Champion: The 1967 World Championship Title Defense

Raganelli probably should have been a double World Champion, given her dominance in the opening round of the 1967 World Karting Championship, which was now spread over three rounds instead of one weekend with three finals.

The championship kicked off in Vevey, and Suzy picked up right where she left off after the 1966 World Championship. However, Karting Magazine didn’t hold back its grievances with the organisation of international competitions, calling the event a "Swiss Farce" and accusing the organisers of black-flagging British driver Mickey Allen to allow a Swiss driver to secure P2. They also reignited their frustration from the 1966 championship, stating that every time Raganelli got a bad start, the race was restarted.

In timed practice, Raganelli logged a 1:13.48, nearly a second faster than future champion Thomas Nielson, who posted a 1:14.30. Peterson was third with a 1:14.46. Once again, Raganelli was in a league of her own.

She won her first heat by 60 yards. In her second heat, she dropped Fletcher, Pernigotti, Allen, and Peters, dominating the race, and the same happened in the third heat. She was once again untouchable.

There is surprisingly little written about Raganelli’s Final win at Vevey, likely due to her sheer dominance. She won the 39-lap race with ease, while most of the action took place behind her. Peterson crashed, and Mickey Allen was black-flagged for allegedly blocking Swiss driver Daniel Corbaz, according to Karting Magazine. Pernigotti rounded out the podium.

Leading the championship comfortably after the first round, Raganelli seemed on course for a second world title. However, this is where her season took a turn. While detailed information is scarce, she had a serious crash during the prestigious Paris 6-Hour endurance event. These endurance races, like the Paris 6-Hour, the UK’s Snetterton 9-Hour, and the Shenington 6-Hour, were highly regarded at the time. As Salamone expressed to me his joy of Shenington 6-hour twice brought him. He also emphasised how dangerous the Paris circuit was, a fact that seemed to catch up with Raganelli.

Going into Round 2 of the World Championship in Düsseldorf, it was clear from the brief report that Raganelli had lost pace. Whether it was a confidence issue or an injury is uncertain, but given her previous advantage, it’s reasonable to suspect the latter.

In front of 10,000 spectators, François Goldstein took the win. The future multiple World Champion was joined on the podium by Ranno and Edgardo Rossi, while Raganelli finished back in 6th place. Despite the setback, she still sat at P1 in the overall championship standings with 88 points. Goldstein was close behind with 84, and Corbaz was third with 83. Heading into the final round on the streets of Monaco, it was all still up for grabs.

Now, forgive me for a moment. The idea of karts racing on the streets of Monaco is something that truly captures my imagination. I’ve never understood the anti-Monaco rhetoric that pervades motorsport. It’s a glorious, unique venue that challenges drivers like no other circuit. In 1967, the kart circuit only used a small portion of the famous track, including the main straight and the section past the swimming pool. While it didn’t include some of Monaco’s most iconic corners, it was still Monaco. However, Karting Magazine labelled the circuit dangerous, with two "diabolical hairpins." Harsh, maybe, but it’s still Monaco. At least it wasn’t a circuit on a field in the middle of nowhere!

As with many karting events of the '60s, this was far from a simple race. Fights, brawls, tears, police intervention, and crashes were the order of the day. Karting wasn’t boring back then, that’s for sure. By the end of practice, the Swedish manager had already gotten into a scrap with one of his team members, setting the tone for the rest of the meeting.

The 1964 and 1965 World Champion, Guido Sala, put it on pole with a 37.48. Raganelli was back in 25th with a 39.40. This was a disaster for her, coming into the event as the championship leader. A decent weekend, in line with her pre-Paris crash form, would have secured her the title, but something was clearly wrong. The Italian team had to pivot to their next hope, Pernigotti, who was sitting outside the top five in the championship but was now their only realistic chance for glory.

Raganelli’s first heat was a disaster, as she ended up in the hay bales on the rolling lap, causing the ambulance to be called. She was OK and bravely continued to race, finishing 22nd. Her second heat saw a slight improvement with a 19th-place finish. In the final heat, she jumped up to 9th place, but Karting Magazine continued to criticise her, claiming she came in tearful after each heat and was consoled by her mother. They mocked the delay before the third heat, stating, “Out comes the mirror and, upon close inspection, minor repairs were deemed necessary. Eye shadow was applied, visor cleaned, helmet polished, mechanics dismissed, and at last she was ready, and the race got underway.”

Due to her poor heat results, Raganelli didn’t automatically qualify for the final and had to go through the B-Final. This race was eventful, to say the least. A Danish driver came to blows with Bertta of Monaco, and a few laps later, Bertta reportedly drove another driver, Forst, off into the bales. A mob of spectators screamed for justice, and four policemen had to guard Bertta for the rest of the event, from which he was eventually disqualified. In the midst of all this chaos, Rossi won the race, and Raganelli finished 3rd, securing her spot in the final.

The final was no less chaotic. As was typical of the time, team tactics were in full force. Pernigotti, Italy’s last hope for the title, had the full support of his teammates, while Goldstein had his Belgian allies.

The first attempt at a start saw Pernigotti drive off into the distance, but a race stoppage for unknown reasons led to a restart. Pernigotti led again after the restart, but chaos soon unfolded. Corbaz had a major crash, badly injuring himself. Goldstein also crashed but managed to restart, though with a bent steering column.

Reports from the event are limited, but disaster struck the Italian team. Pernigotti crashed out, reportedly with his teammates who were supposed to be protecting him. The points listed him as finishing 5th, but it wasn’t enough. In the end, the unexpected happened: Edgardo Rossi, who had to go through the B-Final, clinched the World Championship with an 8th-place finish. Combined with his 3rd in Düsseldorf and 5th in Vevey, it was enough to be crowned champion.

Karting Magazine criticised the multi-round championship as turning the whole thing into a "lottery," but I believe Rossi was a deserving champion. He did what he needed to do, while others faltered. Raganelli finished 23rd. A position closer to 10th would have made her champion.

Bob Smythe, Karting Magazine’s reporter for the Monaco event, couldn’t resist taking one last jab at Susy, stating that she showed contempt by not attending the prize-giving ceremony, which took place in the presence of Princess Grace.

What exactly happened to Raganelli’s performance after the Paris 6-Hour crash remains unknown. Was she driving injured? It seems the most likely explanation, but either way, she was clearly shaken by what had transpired. In normal circumstances, she would have been a double World Champion. Instead, she had to settle for one title and 4th place in the 1967 standings. What could have been.

What Happened After?

Little is known about Raganelli’s racing endeavours after her karting career. In 1967, she toured South Africa with Salamone and Bruno Ferrai.

She was later invited to compete in the 1975 Ladies Race, a support event at the Formula 1 Grand Prix race using Renault 5s, which was won by Marie-Claude Beaumont. It’s possible she raced Alfas, but I have no definitive confirmation of that. It’s also said that she managed her husband Giancarlo Naddeo’s career in Formula 2 and Formula 3, but one thing is certain: she never returned to the limelight.

Several Alfa Romeo Stradale 33 devotees and motoring journalists have attempted to find her over the years, but as I’ve mentioned before, if someone like Raganelli wants to remain out of the spotlight, she will. Who can blame her? The British media's coverage of her success was neither kind nor fair, and that’s being charitable.

Susanna Raganelli is a karting legend, a story that I’ve only scratched the surface of. Much of what’s been recounted here is viewed through the lens of the British media, and I’m certain there is more to her karting journey that we have yet to discover. Why she isn’t more widely celebrated in the modern era is a mystery, but to me, and to many others in the sport, she stands among the greats.

La Suzy, La Suzy, La Suzy!

Alan Dove

Author notes

I've always been a huge fan of Karting Magazine, especially its fearless, no-holds-barred style of writing that I've come to admire over the years. It brings me no pleasure to comment on what they wrote about Raganelli but it’s part of the story and must be told in its entirety, with full context.

In addition, thanks to Mick Pritchard for digging out old Karting Magazines for me to provide this account of her racing. That beer shall be arranged.

Thanks for the work of this story, Alan!

Wow,

Enjoyed reading this Alan!

An important bit of well researched journolism.

Terry Fullerton.